Library

What happens after Agile crosses the chasm

Agile is spreading and changing at such a rate that Cutter’s Business Technology journal devoted two issues to the topic (see references). In the introduction to the first issue, abridged to post on this site, I examined the idea that we have entered the “post-agile” age (read it here).

“Post-agile” means that we are in an in-between period, where the original ideas from the Agile Manifesto have largely been incorporated into our culture, but what comes next has not yet formed clearly enough to be named.

In the introduction to the second issue, this text here, I examine the question of what happens after Agile crosses the infamous chasm and why it will never be fully adopted. Although it appears to stall, it really is moving is two separate waves. But I get ahead of myself. Read on…

What happens after Agile crosses the chasm?

Agile will never be fully adopted everywhere. Geoffrey Moore’s discussion of “crossing the chasm” shows why that will be.

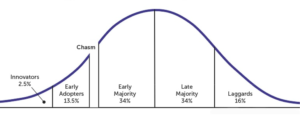

Moore crossing chasm curve

Figure: Crossing the chasm curve, from Moore.

Moore borrows from Everett Rogers, who in the 1970s described the movement, or diffusion, of innovation (ref). He described the 5 attitudes toward a new idea. A small group, the innovators. will try anything new. A slightly larger group of early adopters will see the value and bring it into their lives. Then there is a gap before a large mass of people, the early majority, accept the idea and start to adopt it. Following them by a long period are the late majority, who slowly accept the idea, perhaps unwilling and lethargically. Finally, there are those who really don’t like to change, who resist the new idea until the very end. Some of them may never adopt the idea. This curve is general, for all new ideas.

In the case of Agile, traditional agile has already passed into the late majority. Here is a rough timeline:

- Pre-agile was adopted by the Innovators already in the late 90’s.

- The early adopters picked it up in the first half of the 2000s.

- By 2006, the Agile Manifesto was being used as the basis for contracts, organizations such as the Project Management Institute, Software Engineering Institute and the Institute for Electric and Electrical Engineers were looking for ways to incorporate agile ideas into their platforms.

- In 2009 I gave a talk in which I declared that agile had passed an inflection point, that no longer were people asking “what is Agile?” and more, “How do we use Agile in large, distributed and even life-critical projects?” In other words, by this time, the adoption of agile ideas had moved deep into the zone of the early majority.

- By 2012, the innovators and early adopters, having long experimented with ordinary agile ideas, were moving to Eric Reis’ “lean startup” ideas. By 2015, they have graduated to what they called “hypothesis driven development”, and by 2017, the new, agile product management profession was in motion amongst the early adopters.

- In the years 2016-2019, while the early adopters had moved on with these ideas, “ordinary” agile was making inroads into large, traditional companies, the late majority. Resistant to change and looking to claim the term “agile” without actually changing anything, the dominant sales term in the industry was scaling. “How do we scale agile?”, usually without actually taking on the difficult work of improving communication, speeding delivery, or softening the command and control culture. My view was and still is that this is not a failure of the Agile concept or even the Agile culture, but an ordinary response of the late majority to a new idea that has become popular elsewhere.

- Finally, the laggards, in Geoffrey Moore’s diagram, still resist and will resist to the end. This, again, is not a failure of the agile culture or concept, but an ordinary upper limit to the adoption of any idea. In particular, the Agile way of working requires a certain tolerance of uncertainty, ambiguity and flux that is uncomfortable for many people, and places an ultimate upper limit on who will finally accept to work in this way.

And thus it comes that the next wave of evolution of Agile is growing past the early adopters into the early majority, while the older, baseline agile ideas are still working their way into large, traditional organizations.

The current wave of agile- and post-agile ideas involve taking the agile concepts out of the IT department into HR, purchasing, sales, printing, restaurants, even oil production (as we get to see in this issue). It involves tackling directly the question of culture, how to run organizations with radical transparency into the organization’s financial statements and co-workers’ salaries.

As we saw in the previous issue, there are three big movements these days:

- Faster feedback.

- The use of agile outside of product design.

- Simplification of the agile concepts.

Modern product design groups demand feedback on their ideas within a day or two. They know that each decision today is the foundation for many decisions in the future, and that they cannot guess the reactions of the users correctly day in and day out. Each decision establishes a direction for the future, and so they want to check on these decisions immediately, before putting additional work into what may turn out to be an inferior direction. They are looking for “probes” into the workings of the users, not full deliveries, but just enough to get feedback. They cannot wait two weeks for a Scrum delivery to happen to gather information on these directional decisions.

Changing an organization to be able to deliver probes into the world daily is not easy – it may be as difficult as changing the organization was a decade ago, when they were trying to get teams to give demos every two to four weeks. It is being done by some organizations, but not many, and therefore represents “the cutting edge” of agile.

The second evolution of Agile has been to take it outside of software, and even outside of product design. Even though we wrote the Manifesto for Agile Software Development, within six months we realized that the manifesto had much broader application than just software. Notwithstanding that we had that thought already in 2001, Agile remains stuck in the IT department and in discussions about software products.

The Agile concepts suit any sort of initiative involving decision-making. The agile manifesto really is busy saying that people come up with ideas and make decisions collaboratively, and that they need real feedback to correct and improve those ideas and decisions. In other words, “agile” as a mindset and program suits any white-collar or mental endeavor.

We will see articles in this issue taking agile outside of software, into oil field production, HR and organizational culture.

Finally, as agile penetrated from the early adopters into the early majority and late majority, it became more decorated, complicated, and rule-bound. The early adopters liked the simplicity of the agile manifesto and the space it gave them to talk to each other informally, to follow their instincts. People in larger organizations, however, wanted more clarity into the process, more detail, more repeatability across teams, more certainty and security in what they were doing. They requested, and got, clearer and more detailed protocols and ceremonies. This clarity came at a cost: les speed, less empowerment, less maneuverability, in short, less agility.

I would like to offer that this is both natural and inevitable, it is not a failure of anything, but simply a consequence of the forces acting within large organizations. And, while that is true and inevitable, it is still less efficient and less agile. Thus it is that high-performing agile teams decry these additions and complications.

The third frontier of the new wave of agile is the search for a way out of this dilemma, a way to make things simpler again, while still keeping as much of the benefit of agile.

My own work has been to boil the essence of agile efficiency into just four words: Collaborate, Deliver, Reflect and Improve. I call these the Heart of Agile. (https://heartofagile.com). The Heart of Agile is really just a centering device that allows busy people to remind themselves of the few things are really important. The Heart of Agile was presented in the previous Cutter special issue.

What has been interesting to watch is how these four simple words are at the same time easier to adopt than complicated forumalas, allow more space for individual tailoring in different circumstances, and open up new doorways for investigation.

Among the new doorways we have found are the importance of Human Resource departments, discussion of salaries, annual appraisals, executive bonuses. These are topics not normally associated with the concept of agility, but as you will see from the several articles in this special issue that address them, the implications of working on collaboration directly affects many parts of the organization.

Taking Culture Seriously

What happens when you direct your attention to the topic of collaboration is that you discover very quickly that you need to improve the organizational culture. Collaboration turns out to be a fragile thing. It based on trust, which is even more fragile. It’s enemy is fear, which abounds in the workplace and is a potent killer of collaboration.

Generally, we – including myself here, as well as executives and managers in most organizations – would like to avoid the tricky and painful topics of culture, trust and fear. However, the best companies are working on these topics, lowering fear, increasing trust, lowering punishment, increasing listening and inclusion. Through these efforts, they get more ideas, faster feedback, and faster forward movement on their initiatives. Companies that don’t work on these topic will simply get left behind, as the companies that never adopted the traditional agile mindset have been left behind in the last decade.

What does it mean to “work on culture?”

All initiatives these days are based on ideas and decisions, starting with a few idea initiators and sponsors, and growing through a network of workers until final implementation. Each person makes errors in decision-making at the rate of one error every five, ten or twenty decisions. Any initiative eventually depends on hundreds of thousands of decisions, built one on top of another. That means the final implementation, if done in the traditional big-bang or waterfall style, will contain thousands to tens of thousands of errors.

What we are trying to do with an improved, high-trust, low-fear, low-penalty culture, is to detect those errors – or any form of surprising bad news – as early as possible. This gives the team the maximum time to adjust for that unexpected bad news, and to lose the least amount of time pursuing an incorrect or suboptimal direction. “All bad news early” is a good mantra to have.

Thus it is that we want people to look at all ideas with friendly but critical eyes, to find ways to express their thoughts without fear, and to receive information about mistakes without damage. The organization, as a giant brain, is searching through a hundred thousand intangible decisions for things that might go wrong, in order to improve them early.

Creating such a culture means taking the modern concern for diversity and inclusivity seriously. It means teaching dominant people in the organization, senior technical people, managers, executives and those with dominant personalities, to listen more patiently to those different from them, those who are quiet, shy, fearful. It means changing the reward structures so that members of the same team or same organization are not in competition for the same rewards.

—–

…the end of this fragment. (the rest goes on to introduce the articles in the issue)…

Alistair Cockburn, May 2019.

(Postscript: I continue this thread with a third article, not part of the Cutter series, which I wrote in response to those saying “Agile is dead”. Read it here: Agile is not dead, on the contrary.)

Publication note: This is an extract from the introduction I wrote as guest editor for a special issue of the Cutter Business Technology Journal (Vol. 32, No. 5) on “Cutting Edge” of Agile. You can get The Cutter Edge free at www.cutter.com. This particular special issue is behind a pay wall so you may not see the whole issue. You’ll need to visit their website to decide what to do next, of course. Here are the two issues:

CUTTER BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY JOURNAL VOL. 32, NO. 3, March 2019 : https://www.cutter.com/article/cutting-edge-agile-opening-statement-503026

CUTTER BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY JOURNAL VOL. 32, NO. 5, May 2019 : https://www.cutter.com/article/cutting-edge-agile-ii-opening-statement-504081